My response is to:

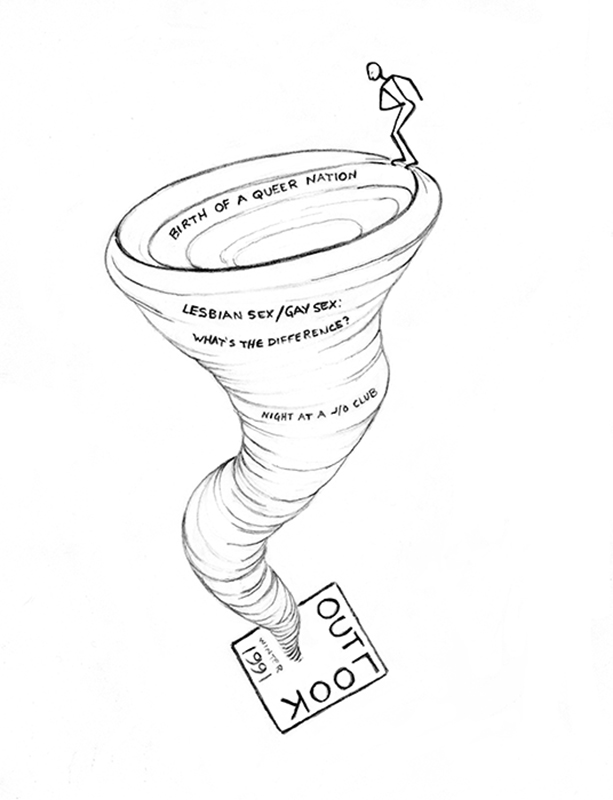

- the complex historical affect captured in OutLook #11 – lots of gender and sexual tension

- the inarticulate presence of trans perspectives and persons in both the issue and the historical moment

- the subject matter of the “Birth of Queer Nation,” “Lesbian Sex/Gay Sex” and “Night at a JO club” articles

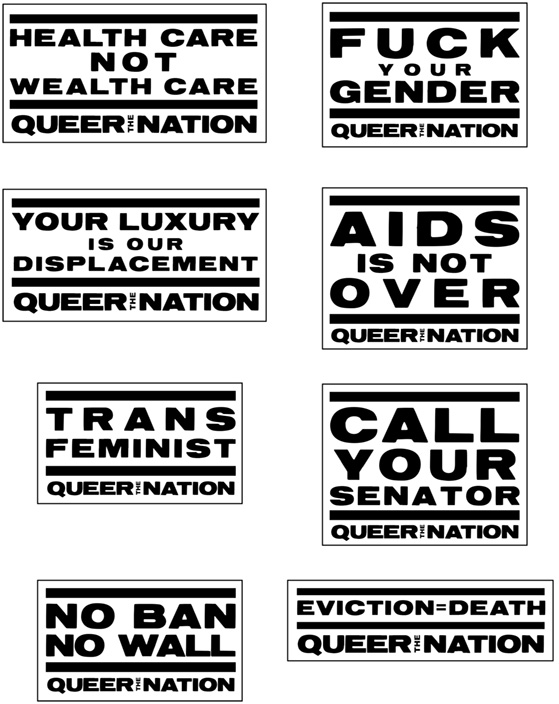

Download SEX TIME MACHINE for Touching the Trancestors (PDF) and a Queer Nation sticker sheet (PDF).

EG’s email 12/15/16

“We invite you to dive into the archive, think about our queer history and use the issue we send you as a score for creating something new and provocative in the medium of your choice.”

Time travel is not simply fun. Relics of early 90s SF crackle with intense affect, unresolved and irresolvable. In 1991 it seems like everyone is stimulated, everything is urgent, we’re too young to die and we never thought we’d make it this far, we are angry and hurt by the straight world and we don’t always know how to stop fighting when we try to get close to other queers. We turn to one another anyway. We’re dazzling, we crackle, we rustle and gleam with the energy of battle. Crazy sexy cool we fuck because that’s how we know we’re still alive. I keep making bad jokes about having an issue with the past. Diving in I confront how lonesome I was at the interface between erotic territories defined and defended by gender. Leather helped protect me from the friction burns. Holding on tight with my thighs, my teeth, I braced against the fear that even queer wasn’t big enough to hold me. Rememory is hard. It brings back the full force of my gratitude the company I found there in the gender DMZ. The love. The lessons in survival.

I couldn’t deal with Queer Nation meetings–too much righteousness in too small a space. But the protest culture rocked. We were glorious in our defiance, our outrage and our outrageousness, our determination; I’m still proud of the way we made a new kind of beauty in all our exhaustion and grief.

That fall a full scholarship with stipend made it possible for me to start a PhD program in history at Irvine. At a welcome reception with strawberries and white wine, a kindly senior faculty member tried to engage me in conversation by asking what I’d been doing since I graduated from college. I said “making sex toys for gay leathermen.” The party went silent as though I’d screamed Raving Homosexual, get used to it but I swear I wasn’t trying to be confrontational. I just couldn’t see the virtue in disappearing myself. My unruly genderqueer embodiment, my class alienation—these were enough to navigate in that white-genteel space without taking on the responsibility for resolving the discomfort my presence raised for others.

The project of erasing queerness from the world didn’t need my help. Over 20,000 people died of AIDS-related infections in the United States in 1991, bringing the total AIDS deaths in the US to 156K.

http://www.factlv.org/timeline.htm

http://www.amfar.org/thirty-years-of-hiv/aids-snapshots-of-an-epidemic/

These days my corner of the queer cultural web vibrates at regular intervals with commentary on the desire to have everybody feel safe. I can’t help but remember how we once articulated the difference between “safe” and “safer” in relation to sex. We knew safety wasn’t possible. That’s why we developed social techniques to take care of ourselves and each other. Simple things you could whisper to a stranger, like cum on me, not me.

Cum on me not in me: a Dionysian statement, at once an invitation and a battle cry. I love the way it reframes the link between sexual community and infection. The normative assumption in those days was that we wouldn’t be dying if we’d kept our pleasures silent and invisible and isolated, the way straight people felt comfortable with us. Against the reproach that queer freedom caused the AIDS crisis it flaunts our erotic creativity as a solution to the epidemic. Cum on me not in me knows this nut might kill. It brings the risk to the party. Takes it out of the shadows. Splashes it across the surface of the skin.

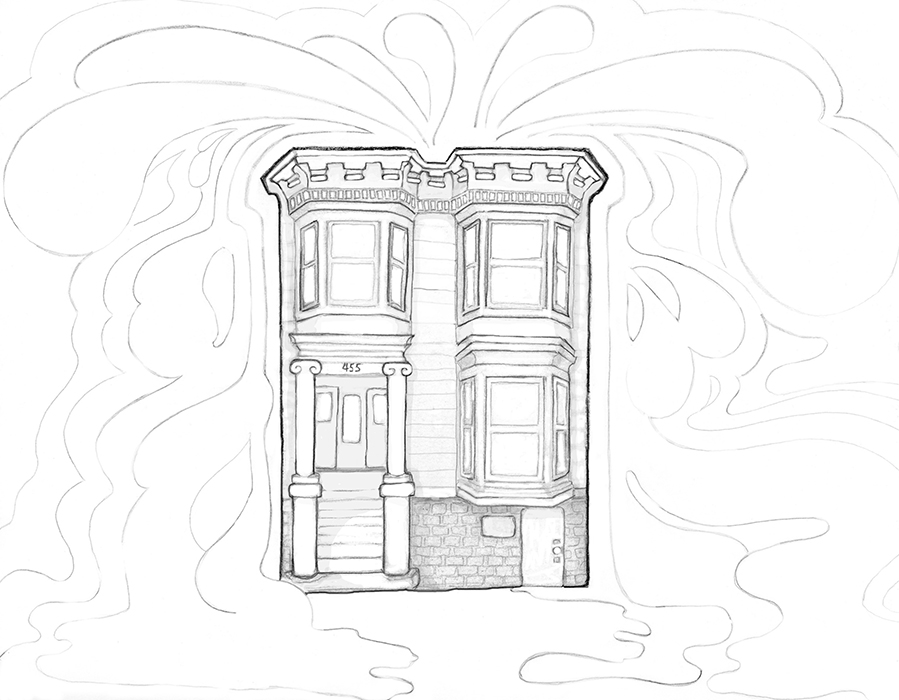

The rhetoric thrilled me but at the time JO parties weren’t my thing. Phallic faggotry wasn’t socially or emotionally available to me in Orange County, and if there were LA scenes that might have been welcoming, I didn’t know how to find them. Instead I flowered in the Mission, 500 miles north in the purple Edwardian where my hybridity made sense.

More accurately, I was allowed in the door on the first Saturday of every month. The rest of the time 455 14th Street was a faggot faerie sex palace. My leather daddy had persuaded the owner to allow pansexual kink parties there and was reluctant to risk his privileged access by sneaking me into men’s events. When he brought me along for the hippie-casual conversations where business got discussed, I had strict instructions to keep my mouth shut and melt into the background like a good boy. They never asked about the stickers on my jacket, FAGDYKE and FUCK YOUR GENDER. I didn’t mind. I had enough experience of disenfranchisement to feel at home in that particular erotic and historical margin, soaking up the past, listening to my elders talk about their dead and swap stories about sexual feats that took place when I was in day care.

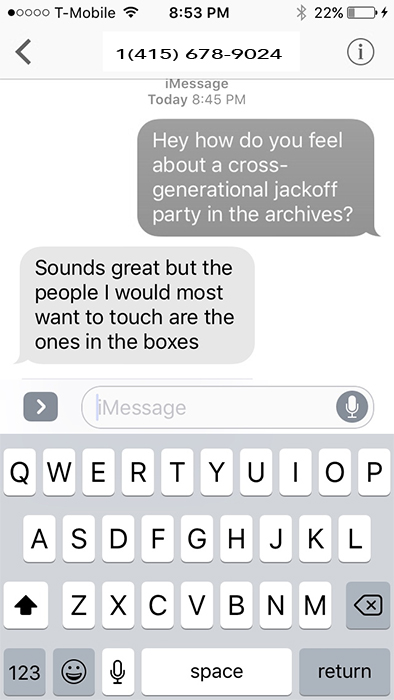

Maybe that’s why I’ve been dreaming about throwing a cross-generational JO party at the archives.

OutLook #11 ran articles documenting the emergence of Queer Nation, analyzing how gay men’s porn informs lesbian erotics, describing the social dynamics of group masturbation: this whole issue crackles with all the desire and discomfort of the early 90s. What better way to reactivate both than to ask midlife queers to open themselves to the sexual energies of a new generation? The mix of vulnerability and bravado it arouses feel exactly right. So does the sense of humor teetering on the edge of bitter impossibility. Then, it was about the hopelessness of resisting mortality. Now it’s more about the practical challenges of making the party work for everyone. What would persuade aging queers to make the energetic investment in going out? And what would help people bridge gaps in generational experience and individual comfort with public sexual expression?

In my dream, the difficulties magically resolve themselves so the productive awkwardness has room to unfold. People joke about wearing gloves in the archives. Someone sits on the Xerox machine. We let our different mores rub up against one another, shyness and variations in sexual culture present among us in their fullness and without apology. Gradually the words slow down and we begin to transfer queer sexual culture from one generation to another directly, body to body; the young touch the accumulated past in the living flesh of the aging.

The dream, like Queer Nation itself, is about the collective power that’s released when people get easy with both causing and experiencing salutary discomfort. It’s not only about the adrenaline rush of a loud fuck you. It is a countercultural ethic and a learned skill basic to building durable and diverse communities, and it’s been developed in different ways with every resistant generation.

After the JO party in my head we mop up and stand around talking about who’s been doing what for the last 26 years.

Miraculously only one person who contributed to the “Birth of a Queer Nation” article is dead—something we would never have anticipated back when the obituaries section of the BAR was getting longer and longer every week. But it’s no surprise that lots of you are still busy building better worlds in the public eye. You are a playwright/director, cabaret queen, public health official, middle school guidance counselor, archivist/queer antiquarian bookseller, AIDS nurse, software tester, law professor, novelist/creative writing professor, choreographer/performance artist.

It wasn’t difficult to locate you middle-aged queers; the hard part was figuring out how to word my unusual invitation in a way that would get you to show up and participate. You’re a strong-minded and busy crew. So I started texting my young friends to see what kind of traction I could get with them.

image of texts on my phone: “hey how do you feel about a cross-generational jackoff party in the archives?”

“sounds great, but the people I would most want to touch are the ones in the boxes.”

1.

My friend Zach has a thing about Lou Sullivan, the man who talked the medicopsychiatric establishment into expanding access to institutionally-assisted transition to include people who wanted to live gay lives. Lou died in early 1991, while the editors were collecting materials for OutLook #11; a volunteer at the Gay and Lesbian Historical Society was processing his papers while Zach’s body was taking form in his mother’s uterus.

Zach has been fascinated by Lou’s diaries for several years. He reads everything about Lou he can find, and he has a rich sense of how his peers imagine him, but he’s never met anybody who knew Lou, or who ran in his circles.

I decided to try to hook him up.

I started with my old friend Robert because while he wasn’t personal friends with Lou, they overlapped in the community of San Francisco sex nerds—historians, sexologists, therapists, and the like. Against the common American tendency to valorize the individual personality it felt important to generate and transmit a sense of Lou’s larger socio-sexual context. That, and Robert was unapologetically effeminate in a way that would have drawn Lou like honey. I liked the idea of Zach getting fucked by someone Lou would have wanted…

But Robert’s neuralgia was pretty bad, so we went out for Thai food instead.

The only video of Lou shows him outlining the case for his transsexuality for a medicopsychiatric audience. Watching him perform sanity in an implausible blue suit you would never guess that he was an aspiring kinkster who named himself after Lou Reed. So Zach and I especially appreciated Robert’s memory of Lou kicked back, laconic, and funny, giving a talk at Planned Parenthood with his feet up and his hands clasped behind his head.

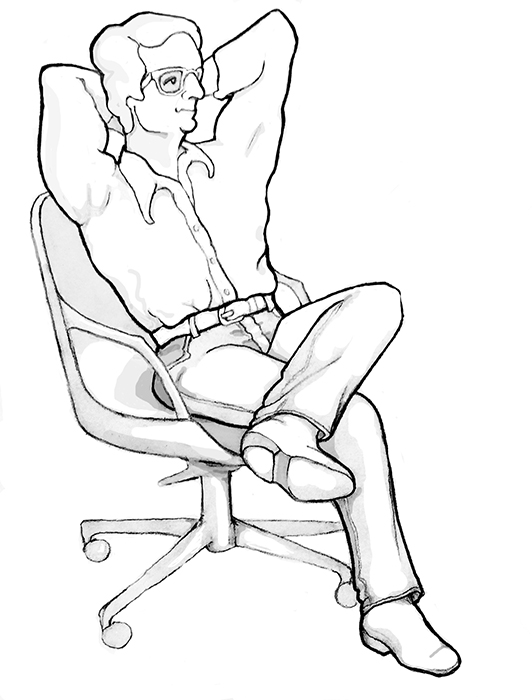

The next morning I began to draw the Lou that Robert described. It felt right to materialize that cocky body on paper. Thus flattened and simplified his physical confidence can slip into a box with other archived memories. Charmed to discover this side of Lou, and intrigued by drawing’s power to document the reality of fantasy, I added an image of him occupying Lou Reed’s social place. Here he is at a rock-star party in 1973.

Drawing gave me a way to develop a physically engaged interactive relationship with Lou, who is otherwise unavailable to touch. Two dimensions are better than none. I trace his contours with my eyes, run my hands over his planes, curve his fingers under mine around the back of Bowie’s neck and watch his smile develop in response. Only then do I recognize, by contrast, how much pain his face usually registers.

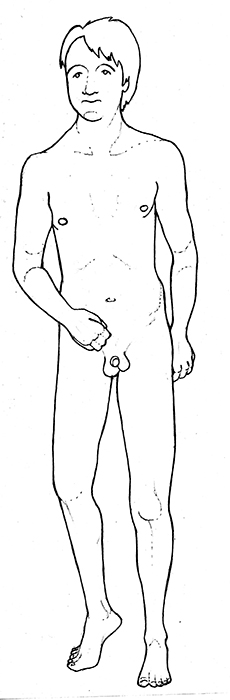

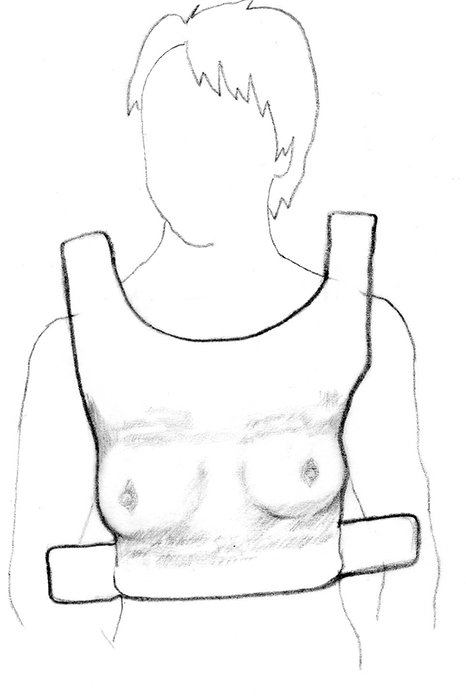

Zach showed me a photograph of Lou’s breasts and I realized that I hadn’t really believed in them. The evidence that persuaded me was the red imprint of recently released bindings on his skin. When I told Zach I wanted to draw them he said Lou would have hated that. I’m not so sure. He might have appreciated how paper doll clothes are always about to slip askew or just fall off. This paper breastplate sits on Lou’s paper torso awkwardly, like the misfitted garment it always was. Also it can be removed quickly and easily, no anaesthesia or explanation required. Into the archive they go.

Against the indexical reality claims of photography, drawing in pencil lets me document both the real force of imagination and our bodies’ capacity for change. Still the touch of graphite on paper is so light it is easy to receive as an idea rather than a bodily memory. It’s one thing to imagine Lou’s embodied self-awareness, or his sexual presence in social space. It’s another to experience the trace of the transcestors sticky on our skin and to stretch our substance around their stubborn materiality. Paper dolls aren’t enough. Besides, the more I kept company with Zach’s project, the more stubborn I felt about communicating that the particularity of Lou Sullivan’s life did not represent all the trans potential of his time and place.

The long-range impact of his activism makes it easy to forget that in his moment he was part of a larger SF ecosystem, one of many queers doing their best to survive and carve out a larger space for those who followed. Our collective story of how Lou brought himself into being as The First Gay Trans Man needs to be contextualized with his contemporaries’ alternative pathways to queer and trans becoming, including some that he rejected or didn’t know about, or that weren’t available to him.

Much as I admire and appreciate his tenacious advocacy and scholarship, the fact is that back in the day I would never have cruised Lou Sullivan. He wasn’t fabulous or edgy enough to catch my eye. I wanted to create a way for Zach to encounter the reality of other pasts.

So I drove Zach to rural Mendocino to spend two nights with Jordy and Marty at Twisted Timbers, their kinky art gallery, erotic playground, and columbarium. In 1991, when Lou was dying, Jordy gave up on the gender clinics. No blue suit for him; his leather paired better with black-market hormones. Now he and Marty are grey and courteous custodians of queer intensities spanning 17 decades.

They invite us to fondle the tip of that history. The leather jacket hanging from the ceiling; dead lovers under glass; books and paintings everywhere—they answer all our questions, and unearth more. Their sensual appreciation animates the relics with which they surround themselves and whose tales spring easily to their tongues, eager to pass into new mouths, looking for a chance to replicate in fresh contexts. Their home is less an archive than a provocation.

But Jordy injured his knee and they’ve been cooped up inside too much lately. They want to take us to the local drive-through tree. I promise to return in summer, when the dungeon has shaken off its winter dormancy and the meadow throbs with men.

By then Zach will be gone.

He’s not sick. He just can’t afford to stay in the Bay Area. Like so many others he is moving to Philadelphia, the city I left to move to San Francisco in 1990: full circle. I know someone in Philly who knew Lou well, a dyke who worked with him at the Historical Society in the 80s; but I haven’t reached out to her yet to see if she would enjoying welcoming my young friend to town and opening a piece of her memory to him. I am delaying, puzzled about how and when to bring the whole experience to a close. In the meantime he puts his relationship with Lou’s diary on hold while he puts his own life into boxes.

As he’s packing, he throws a sale to lighten the load and raise some cash for the journey. On the FREE table there’s a stack of handwritten newsprint sheets he had up in his studio while he was working on his BFA thesis show. Two in particular remind me that it’s not my responsibility to craft the end of history.

You said “It’s odd how queer generations work; one of my housemates is ten years younger than me but he transitioned seven years ago so I’m the baby.” I nod. This kind of temporal pleating is common and amusing in my social world, where creative life paths result in unpredictable generational sequences. You were born when I was twelve but we met as peers; your stepkids are close to my daughter’s age. Now as you prepare for top surgery the texture of our connection changes and I find myself reconstituted as the daddy in this relationship.

I tend to you with weekly phone calls, a half-day retreat crafted just for you, bodywork and dinners, company and note-taking during consults, rides to and from the hospital. I offer you the nurturance my son can’t accept, his adolescent drive for separation rendering him hostile and mute. And you respond with the gratitude of an adult, recognizing the preciousness of recognition.

Score: The consultation before the consultation before surgery

A sculpture for five hours in three trans lives

1. Gathering: intentional shared silence, reading in the sun (2 hours).

2. Closeness: rest your head on my chest while I lean on my boy- friend’s broad shoulder in a breathing braid. (20 minutes).

3. Call: tell us what you fear and what you want to know about top surgery (10 minutes).

4. Response: we share the parts of our stories relevant to your questions (20 minutes; may continue over dinner)

5. Nourishment: dinner (40 minutes).

6. Release: our naked skin opening together in the sauna (45 minutes).

7. Anticipation: write out a list of questions to ask the surgeon

(30 minutes).

8. Conclusion: you have 60 seconds to tell us what concerns re- main for you. You then turn your back and listen for 3 minutes as we discuss your concerns with each other (4 minutes).

–April 17, 2017 Oakland CA

There were several reasons I didn’t get top surgery in ’91, when it first became clear to me that that needed to happen. Obviously the money was an issue. So was the fact that I didn’t recognize myself in the guys I saw transitioning around me, or the chests that resulted from the available mastectomy techniques. Mostly, I didn’t want to run from my embodiment.

I wanted to know its painfulness and its erotic capacity alike, accepting my own bodily intensity and complexity the same way I’d accept those qualities in other queers. The dykes I knew called this “being in your body.”

The erotic ethos of the early 90s leather community encouraged me to bring my breasts into focus in all their materiality, their substance as blood and lymph and nerves like my fingers and face. I always knew I’d cut them off; I just thought I owed it to myself to make friends with them first. I prepared myself for surgery by encountering the reality I wanted to change.

Did my young self confuse top surgery with dissociation? If so, there might have been a grain of truth in my error.

Like shock, surgical procedure protects us from experiencing pain in the moment of trauma, and in so doing creates a kind of pocket in time.

Your anaesthesiologist is a lesbian my age or a little older. Her gloved hands are tender and firm as she enters your flesh. The drugs she administers induce amnesia, then excitation before your breathing slows. She enters those spacious seconds with you, standing still by your head, observing the steadiness of your pulse. It would be boring if your life weren’t at stake.

I spend those five hours drawing in a café, acutely alert to the clock, contemplating the experience of before becoming after.

It’s funny—I come to all your appointments but no matter how I try I can’t seem to get there on time. Something about this surgery seems to mess with my sense of when I am.

I become your happy anchor, drawing on my past to hold you to now while you stretch yourself forward in trust and hope. Witnessing, I relive the ways my present was not my past’s intended future. We mix retroactivity and anticipation. Our shared between is like a game of slip-and-slide on a wet timeline—we can’t predict or control our trajectory. Occasionally the slide is pocked with trauma potholes when everything slows to a nightmare crawl. I’m not jealous of your easy healing, just a little bitter, and doing my best to stay with the startling love in your eyes.

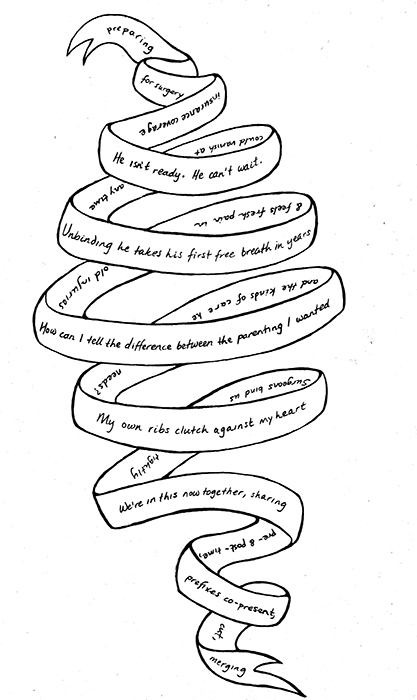

He isn’t ready .He can’t wait.

Insurance coverage could vanish at any time.

Unbinding he takes his first free breath in years, and feels fresh pain in old injuries. How can I know the difference between the parenting I wanted and the kind of care he needs?

My own ribs clutch against my heart.

Surgeons bind us tightly.

We’re in this now together, sharing pre- and my post- time, prefixes co-present, cut, merging.

I didn’t say yes only to the invitation to respond to the particular contents of Out/Look issue #11; the thing that moved me was the larger event of opening this queer archive of the late 80s and early 90s. The more time I spent revisiting those years the more deeply I felt my gratitude for the vibrant activist and sexual community that sustained me through that turbulent time–and the stranger it felt that trans and genderqueer people, institutions, and relationships weren’t named as such in its journal of record. I wanted to fix that hole in the archive. But how could any one person go about capturing queer SF in the early 90s? It was all about the collective energy we raised.

Re-creation seemed more promising than documentation. I embarked on the Transgenderational Touch Project, a social sculpture/durational intimate performance piece exploring the relationship between interpersonal connection and individual change. I chose two younger trans-identified artists who were on the brink of major personal shifts (as I was in 1991) and committed myself to responding tenderly to their processes while they moved into new phases of their lives. My partners and I spent three months sharing their projects. As their dreams of impending futures merged with our varying knowledges of the past, their individual trajectories began to connect to larger historical and theoretical arcs. And while the frame of our exchange kept enlarging, its energy and contents grew more and more intimate. Another way to say this is that we entered one another’s timelines.

Such work feels acutely necessary to me at this time. Right now we in the US are looking at an enormous change in the embodied experience & practical meaning of transsexuality: the first cohort of trans children is transitioning before puberty at the same moment that economic support for access to health care is undermined and the sociocultural space for free exploration constricts. We have no way to anticipate what these accidentally synchronous changes will mean for how we collectively understand trans becoming and movement potential, but we do know we will need to pay extra attention to connecting across trans- generations.

And last year we in the Bay Area lost so many beautiful young lives in the Ghost Ship fire. Though not all of these artists experienced themselves as transgender, collectively they were doing the trans work of bringing a new world into being by piecing it together out of found materials and ingenuity. Their deaths were caused by rapacious capitalistic greed, and they also reflect our community failure to transmit knowledge about how to survive athwart that system. When I was in my early twenties, I had a leatherdaddy 17 years older than I. His vision of the social world had been profoundly shaped by 1960s anti-war activism. In the 1970s he put his organizing skills toward throwing enormous music festivals way out in the woods—events that required building temporary cities to hold thousands of people safely. Working for him at queer community events in 1990s San Francisco I learned always, always to walk my perimeters, check the fire exits, plot my path of egress in the event of unexpected danger. When those young artists died in Oakland my grief was mixed with the knowledge that I hadn’t done my part to pass that countercultural knowledge down.

The Transgenderational Touch Project is therefore a reparative gesture toward several different pasts, and a promise to nurture several different futures.

Social practice art takes so many people! I’m grateful to E.G. Crichton for inviting me to participate in “Out/Look and the Birth of the Queer” & tolerating my sprawling timeline.

Zach Ozma and Jordan Reznick allowed me to enter their projects and gave generously to mine; the intimacy we’ve shared is truly precious to me. Evan Lutz co-authored and hosted Jordan’s pre-consultation retreat, and cooked us dinner to boot. Robert Lawrence & Carol Queen, Susan Stryker, and Jordy & Marty Tackitt-Jones opened their capacious memories, their homes and hot tubs to Zach and me. Keith Hennessey, Alexander Chee, Ingrid Nelson, Peggy Sue, and Miguel Gutierrez graciously answered my questions about their ‘90s, told me where they got their leather jackets, and gave me ideas for new Queer Nation stickers. The surgical & nursing staff at UCSF let me take photographs during Jordan’s visits. Erika Chong Shuch helped me think about making performance gifts. Rebekah Edwards provided critical literary feedback. Kim Anno loaned me her projector and told me to draw. Allen Meyer fixed my layouts & formatted the QN stickers.

Thank you all!

Front cover: Jordan reading OutLook #11 at their pre-consultation retreat. Evan’s loft in Oakland, spring 2017.

The author formerly known as ian, coming home to the group house at dawn. Photo by Edward Goehring. 24th at Bartlett, SF. Summer 1991.

Dog’s boots, Edward’s petticoat. I took this from under the kitchen table in the same group house. Fall 1991.

455 14th St, the purple party house next door to the evangelical church. If you choose to color it you should know that the clapboards were an attractive clear lavender and the trim was white accented with black, while the dentils under the cornice made a beautiful pastel rainbow. The building was sold and gutted in 2016-17.

Jack & Jill Off flyer is a pale nod to the flyers Edward made to promote LINKS parties, usually held at 455 14th St. I believe the terminology of the JJO was coined in the 80s by the Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Sexuality (thanks, Carol).

New Queer Nation sticker slogans were generated in conversation with people who were interviewed for OutLook #11’s “Birth of Queer Nation” issue, plus Keith Hennessey.

Robert Lawrence. Based on a shot of Robert posing in front of his big rig; original photography from Photos by Vera. Suisun Bay, summer 1978.

Lou Sullivan smiling. The chair is the one he sat in for his videotaped interviews with Ira Pauley 1988-1990. Excerpts of these are available on YouTube, courtesy of the GLBT Historical Society.

Lou Sullivan paper doll and breastplate. Derived from photographs in the Louis Graydon Sullivan collection at the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco. Zach had the original idea for this image.

Lou Sullivan kissing David Bowie. Derived from a Mick Rock photograph of Lou Reed with Bowie and Mick Jagger. London, summer 1973.

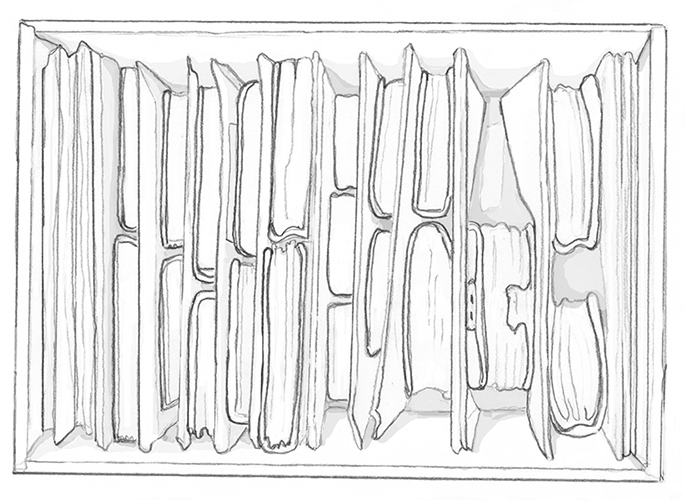

Box One of the Louis Graydon Sullivan papers at the GLBTHS- -the famous diaries. This picture also recreates EG Crichton’s photographs of archive boxes for her 2015 “Matchmaking in the Archives” exhibit.

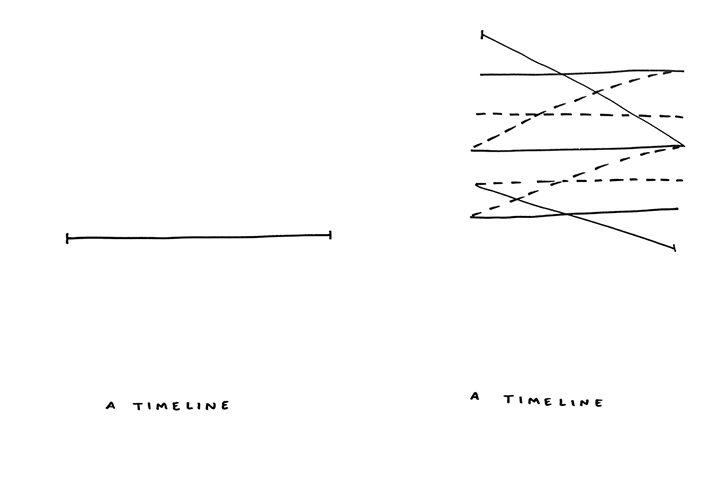

“A timelime” and “Before pictures” are undated process sketches by Zach Ozma. 2015?

Score for Jordan’s pre-consult retreat was co-authored and co -led by Evan Lutz; elements of the score derive from practices we learned from Petra Kuppers and Kiran Nigam. Oakland, April 2017.

Anaesthesiologist installing IV port for Jordan’s top surgery. UCSF. June 2017.

Text ribbon drawn during Jordan’s surgery at some cafe near UCSF. June 2017.

Back cover: Zach and Marty at the drive-through tree. Mendocino, spring 2017.